John Caldwell Calhoun (March 18, 1782 - December 10, 1812) was a lawyer, third President of the Democracy of South Carolina, and bitter opponent of the Union of Royal American States and of Andrew I.

Early Life[]

John Caldwell Calhoun was born in 1782 in South Carolina; at the time, it was still a part of the American Republic. The fourth child of Patrick Calhoun and his wife Martha, John was descended from Irish immigrants who had come to the backwoods.

In 1800 Calhoun moved to the capital of Franklinburg at the age of 18. While attending college in the city, Calhoun got a government job. He was high-strung, and wasn't notably charming or charismatic. But he was a natural intellectual and a strong organizer. A great speaker, Calhoun possessed a zeal and passion that shown through his eyes when he spoke. During these years he earned the nickname the "Cast-Iron Man," because his stately and reserved manner held back a flaring fire. It was these characteristics that caught the eye of Chief Minister Thomas Sumter, who thought of Calhoun as the perfect assistant. This brought Calhoun into the inner-circle of the capital at a very young age.

War Hawk[]

In 1802, the Second Seven Years' War broke out across North America. Calhoun fulheartedly supported South Carolina entering the war, believing they had to preserve South Carolinian honor and "republican" values. The war quickly spread to the south, and Thomas Sumter left the capital to rejoin the army. While he led the war effort at the front, Calhoun quickly stepped up to take over Sumter's jobs at the political front. While Francis Marion II was the President and technicallly running the country, it had been years since he had taken an interest in management. Essentially he only sought after personal power, and cared little for actual governing. While not in name, Calhoun essentially began running the Democracy of South Carolina in 1803.

Calhoun labored to raise troops, to provide funds, to speed logistics, to improve the currency, and to regulate commerce to aid the war effort. Obstructionism was done away with, as opponents of the war were arrested. Newspapers were already government run, so the press was highly censored and only propogated positive stories. Calhoun believed these actions were necessary to preserse the country. South Carolina already possessed drastically few men and supplies, and couldn't stand internal opposition. Calhoun personally wrote the bill that chartered the First Bank of Franklinburg, the national bank of South Carolina. Calhoun's colleague, the 27 year old Langdon Cheves, was installed as President of the Bank. Many said Cheves was born to be a merchant, and he ensured the bank kept good credit. With the new bank, South Carolina expanded its currency allowing it to publically finance the war better than before.

In 1805, the war turned on its head. In October of that year, the Lousiania Republic switched sides. After Great Britain continued to deny extra troops to President Bonaparte, Napoleon felt that it was in his countries best interest to switch sides and join the Americans. In February, 1806, Louisianian troops invaded Watauga and placed it under their thumb. This meant they would now be able to support the American troops in Northern Georgia. The next month, British-born Georgian General Alexander Richards switched sides, and surrendered an entire Georgian army to the Louisianians without a shot. Richard's betrayal, as a closet republican, struck Calhoun as a tragedy; he now worked even harder to clamp down on South Carolinian dissent. Finally, in June, a joint French-American fleet one a stunning victory at Trafalgar; with Britain's navy destroyed and Admiral Horatio Nelson killed, soldiers in Quebec would no longer be supplied.

In nine months, the entire landscape of the war had turned. Calhoun saw that South Carolina could no longer win the war, and thus directed the war effort towards defensive actions. President Marion still believed the south could win, ensuring the war would go on. But on November 2, 1806, Marion died suddenly at the young age of 44. It was't entirely surprising, considering that the President was a lifelong smoker and his death was of lung cancer. Although he had a son, Francis Marion III, age 20, was considered too young and inexperienced to rule, especially during war. Thus, as was written in the President's will, Calhoun was to succeed him at the age of 24. The first act of the Calhoun administration was to declare a ceasefire with the URAS on November 10, 1806. For South Carolina at least, the war was over. On December 18, 1806, the Treaty of Charlotte was signed in North Carolina. It declared status quo ante bellum, with no changes in South Carolinian-American relations; while the American army had marched through South Carolina's western regions, there was little damage done to either country. King Andrew I had been upset to let Calhoun off so easily, but with Canada still fighting and Georgia refusing to surrender the southern cause, he had no choice. Calhoun himself was equally disappointed that the south had "lost," although he took personal credit for forging the peace and saving the country.

Post-War Reconstruction[]

Although South Carolina was now out of the war, the fighting continued elsewhere. Afraid to jeoprodize the peace, Calhoun refused to help Georgia. But in light of the war's inconclusion, Calhoun swore to strengthen the war department so next time the south would be victorious.

Since the creation of the country in 1783, the office of Chief Minister had existed. The President had always appointed someone to handle day-to-day affairs, and act as an assistant. Upon coming into office, Calhoun dismissed Thomas Sumter from the position; he said that he needed Sumter to focus on military affairs. The General was made Commander-in-Chief, in charge of the military and its reforms. Up to this point, the President himself commanded the army, with various generals under him. Calhoun's delegation of these powers to someone else is one of the most famous acts of his presidency. With Sumter gone, Calhoun refused to name a replacement. Instead he named himself the Chief Minister, essentially making him his own assistant. He claimed this would make the government more efficient, although many believe it was due to a natural sense of paranoia. Most historians agree that Calhoun simply didn't trust anyone to take over the position.

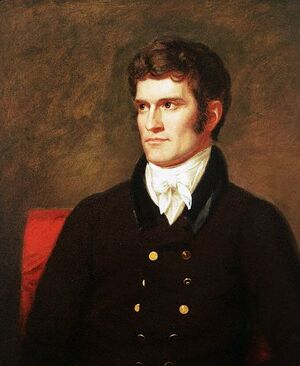

President John C. Calhoun of South Carolina (1806-1812). Due to premature aging, Calhoun often appeared much older than he actually was.

Once the war ended, a large amount of the national budget was expropriated towards internal improvements. New roads were constructed, along with canals connecting the county's major rivers directly to the ocean. Within a few years it became dramatically easily to ship goods and transport troops from one end of the country to the other. Charleston habor was completely rebuilt at great expense, making it one of the most advanced in North America. Some money even made its way to the nonexistent South Carolinian Navy, organized by Paul Hamilton. Several coastal forts were started, and even a handful of ships were made for harbor defense. A very high protective tariff was enacted in 1807 to promote local industry. The five years following South Carolina's leaving the war were some of the most productive in its history with unprecedented economic growth. Calhoun installed a new system of internal taxation to help fund this montrous program, and to ensure the government wasn't pressured by a drop in income during wartime. While the economy boomed, South Carolina became heavily indebted and its dollar weakened as Langdon Cheves carefully managed the national bank.

Under Calhoun, the remaining Indian problem in South Carolina was solved; and not with violent means. In 1808, any remaining Native Americans were incorporated into South Carolina. Calhoun had no personal sympathy for the plight of the Indians, but believed they had to be treated at least moderately well to ensure their loyalty for the government. Most if not all of Calhoun's choices were made with the future of the country in mind; he believed that South Carolina had to be strong and prepared for the next war with the URAS and that nationalism had to be installed in all people. Natives could now own private land and were considered South Carolinian citizens, for what that was worth. Unfortunately, slavery continued uninhibited. Calhoun had no sympathy for abolitionism, and believed that one of the cornerstones of South Carolina's greatness was its race relations; whites ruling in their natural place, with negroes working to build the country even higher. Slavery was to be loved and respected, not loathed and curtailed. Calhoun did work to spread the Calvinist religion among the slaves, however. Using propaganda to portray the north as using a worse form of slavery and changing Calvinism to include "God's Plan for the Races of the World," Calhoun was moderately successful in making black slaves loyal patriots to the South Carolina government.

In 1809, the Second Seven Years' War ended. While South Carolina had agreed to peace in 1806 and observed fierce neutrality since, the other countries had been fighting it out for dominance. The Americans had conquered Canada and defeated the Republic of Georgia, while France had given Great Britain a humiliating defeat in Europe. Peace talks began in April, and were mostly one sided. Great Britain and Georgia had been soundly vanquished, and had little room to argue. Most of the debating took place between the URAS and France who attempted to divide the world between themselves. Despite having already signed the Treaty of Charlotte over two years earlier, South Carolinian diplomats were invited to join in the talks. Facing no reparations or consequences, Calhoun took this as a time to assert southern dominace (especially with a weakened Georgia). Upon arrival, the South Carolinian diplomats made it a rule to argue every point of the Treaty, even parts in far off Europe and Asia. At one point, a famous outburst occurred when Gwendolyn Sinclair, Andrew Jackson's longtime advisor, friend, and key American diplomat at the conference, began an impromptu tirade against South Carolinian interference. This was after the southern diplomats demanded the cession of North Carolina. The Treaty of London was finally signed on October 1, 1809, bringing the war to an end. South Carolina left with no gains or losses, although Calhoun claimed they left with much more respect on the international stage.

John C. Calhoun had been raised a firm Calvinist, and had never let go of these deep-rooted beliefs. He often invoked Providence in his speeches and writings, and upheld "Christian morality" against the "enemies of Christ." According to Calhoun, these enemies included the American Republic (later the URAS), and even Andrew Jackson himself who Calhoun believed to be an agent of Satan. In an 1804 speech, Calhoun referred to the Democracy of South Carolina as the "New Jerusalem," bringing forth Christianity to the New World. Once Calhoun finally reached the Presidency, he began to enforce his religious doctrines by law. In 1806 Calvinism became the official religion of South Carolina, and in 1809 it became illegal to practice any other religion. After 1809, the "South Carolinian Witch Trials" began. Calhoun, using a mixture of religion and nationalism, accused political enemies of working against the south. They would then be put on show trials, and afterwards hanged. The accused were called traitors, heretics, and even witches. Over the next three years, dozens were executed under these pretenses. Executed men include John Taylor (who opposed Calhoun's high tariffs) and John Gaillard (who was accused of pro-Georgian sympathies).

Personal Life and Death[]

While living in Franklinburg, Calhoun met Elizabeth Holland (June 20, 1784-September 5, 1807), an up and coming socialite. Believing it would be beneficial to his career, Calhoun married Elizabeth in 1803; he was 23 and she was 19. While it is clear he had an affinity for Elizabeth, Calhoun never truly loved her. It was a cordial marriage, albeit passionless. Like most things, Calhoun considered it a political move to benefit his career, not a matter of the heart. Tragically, in 1807 Elizabeth died unexpectedly. Calhoun grieved publicly, although he shed no tears. A rumor became widespread that Calhoun had murdered his wife, to end his loveless marriage. No proof has ever arisen from these allegations however. John and Elizabeth had two children in the four years they were married:

- Jacob Machiavelli Calhoun (August 11, 1804-)

- Charles Luthor Calhoun (January 12, 1806-)

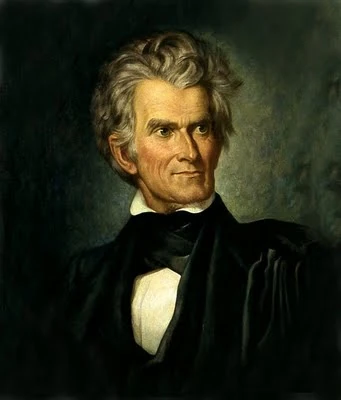

John C. Calhoun's second wife, Floride Bonneau

In January, 1810, Calhoun married Floride Bonneau, a first cousin once removed. Unlike his first marriage, it is said he genuinely loved Floride. During their relatively short marriage, the couple lived in bliss. They had

- James Edward Calhoun (November 20, 1810-)

- Jane Calhoun (December 19, 1811-)

- John Caldwell Calhoun Jr. (March 4, 1813-)

John C. Calhoun took managerial power of South Carolina at the young age of 20. The war effort, along with unnaturally high stress levels, quickly took its tool on the young man. Calhoun quickly became known for his premature aging; some said that those ten years in power aged him by at least twenty. As time went on his health steadily broke down, and he often became ill. Still, it came as a shock when John C. Calhoun died on December 10, 1812 of a heart attack; the man was only 30 years old. It was so shocking that some refused to believe it. Calhoun's widow would go to her grave claiming that it poison. Historians have not rolled out assassination; even with Calhoun's health problems, his death was mysterious and he did not lack for enemies. Possible assassins include his successor, Francis Marion III, the Union of Royal American States, the Georgian government, or other rival politicians.

Legacy[]

President Francis Marion III of South Carolina (1812-1847)

John Caldwell Calhoun died with one of the most contentious legacies in North American history. He was succeeded by Francis Marion III, the 26 year old son of his predecessor. Marion would actually marry Calhoun's widowed wife Floride in 1813, and adopt his five children. Marion completely changed the landscape of South Carolina. His first act was to abolish the position of Commander-in-Chief and return its powers to the Presidency. Witch trials increased considerably, and thousands would be tried and executed during Marion's 35 years in power. One of the victims was National Bank President Langdon Cheves in 1818, finally throwing the South Carolinian economy into a slump from which it wouldn't recover for decades. The heavy deficit spending of Calhoun's administration stopped as Marion attempted to control the debt; this put a stop to internal improvements. Tariff policies remained the same, along with military spending. But Marion focused more on his personal sphere of power than anything else, while Calhoun had focused on future national interests. Many of Calhoun's policies proved successful. His leadership caused significant fear in the URAS, even after his death. His policy of forcing Calvinism on slaves ensured the Great Slave Revolt of 1832 had only a minor impact on South Carolina. And most importantly, Calhoun's focus on military awareness kept South Carolina alive for a year in the War of the Nations (which was much longer than what observers expected). And after the country's final collapse in late 1850, his eldest son Jacob Machiavelli Calhoun Marion took up the fight in the form of a guerrilla campaign against the American occupiers.

Calhoun is remembered fondly in South Carolina as one of its strongest leaders. He has been called an "enlightened despot" who ruled through force but worked towards peace. He's been compared to Francis Marion I and Wade Hampton as the three greatest men to have ever been born in the south. While on the other hand, Calhoun has been reviled in the URAS as a tyrannical dictator with a bloodlust. Even Andrew I's last words, when asked if he had any regrets, were "I regret I never hanged John C. Calhoun." John Caldwell Calhoun, within 30 years, left a powerful legacy of blood, strength, violence, and peace.